Not through me, face it in yourself

In a board meeting

There were fifteen people in the room. The Board was having a regular meeting to think about how they led a large and complex organisation. The scene about to unfold had its origins two months earlier in a development workshop for senior managers.

In that workshop, people had talked about how differences played out in their divisions and teams and how these differences were playing out in the workshop. They were talking about differences you can see. The catalyst for the conversation had been a session led by a community activist and leader. He epitomised what it was to be constructively awkward; to speak up about what and who may be silenced and ignored in the way everyday life unfolded in communities. He talked about how abstract notions of power played out in his life and that of his community. He spoke kindly and intensely. He enabled people to go where the difficulties might be in this group of talented leaders, serving a large and diverse community.

Adisa started to talk about his experience of being a black manager. He described moments of being isolated and ignored; seen as capable but never fully part of things. An outsider, inside the organisation. He was clear, concise and communicated his utter exhaustion. Every day required a massive effort to fit in and not retaliate. The person next to him began to cry. She was white. ‘I never realised’. Others were quiet. It cost her to step away from her professional role in HR to say in effect she had no idea this was how it was for him. She said she was sorry. He accepted this with grace.

Back at the Board meeting. We had invited some of the managers from the development workshop to join them in the afternoon. The purpose was to talk about how unprofessional behaviours (code for bullying and incivility) silence people and issues. We aimed to facilitate a conversation about work as done and experienced. To explore any difference between this lived experience and what the board imagined people did; assumptions upon which work was prescribed. Shortly into the conversation a board member turned to Adisa and asked him what they needed to do to stop marginalising people (like him).

If time could slow it did. A signal that what had been an abstract conversation was about to be enacted in the room. Adisa spoke. He said he wanted people to stop behaving as if he knew the answer to racism and discrimination. It was not his problem. He was on the receiving end of these behaviours. He understood we wanted to understand why discrimination occurred in the organisation, despite the campaigns to stop it. He knew we knew these behaviours hurt people. However, why did we insist on asking him about what needed to be different; when it was our lack of insight into our behaviours that contributed to the problem of discrimination he felt? He needed people to stop working on this issue through him.

I felt uncomfortable. The discomfort of a truth arrived. The discomfort of being caught out. The Emperor is naked, so let us stop pretending; notice the groupthink and the comfort of our conformity1See: Kellerman, B. (2004) Bad leadership. What it is, how it happens, why it matters. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Harvey, J. (1988) The Abilene Paradox: The management of agreement. San Francisco, Jossey Bass.. We, the white people were being called on our unspoken collusive arrangement about how to think about discrimination around here. Adisa was calling attention to our assumption that hearing about his experience of discrimination would be enough to understand our motivation to discriminate. He was, in fact pointing to our intention to talk about discrimination and while keeping our assumptive scaffolding, embedded in the organisation’s fabric, intact.

As the moment past, we set up a series of conversations, to explore what people were thinking and feeling about discrimination. There was some reluctance interpreted as counter-resistance2‘Counter resistance’ is that which seeks to counter the innovation, change or new data. To undermine the emergence of alternative narratives. Tactics may include argument, concept rejection or demand for quick and comprehensive spread, delays in responding, silencing other staff and presence or absence from meetings.

See: Caygill, H. (2013) On resistance. A philosophy of defiance. London, Bloomsbury.. A wish to put some space between what people now knew and its translation into (disturbing) insight. It felt hard to give up the ease of second-hand learning and there was some understanding this was not the critical reflective practice3See: Bolton, G. and Delderfield, R. (2018) Reflective practice. Writing and professional development. Sage, London. required to change behaviour. Learning at this level makes us anxious. Anxious about our status and competence as learned professionals. That is why resistance is an understandable response when our assumptive frameworks are put in doubt4See: Argyris, A. (2000) Flawed advice and the management trap. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Argyris, C. 1991. ‘Teaching smart people to learn’. Harvard Business Review. vol. 69(3), no. May – June, pp. 99-109.

Argyris, C. 1986. ‘Skilled incompetence’. Harvard Business Review. vol. 64(5), no. September – October, pp. 74-79.. Even if we choose to do this.

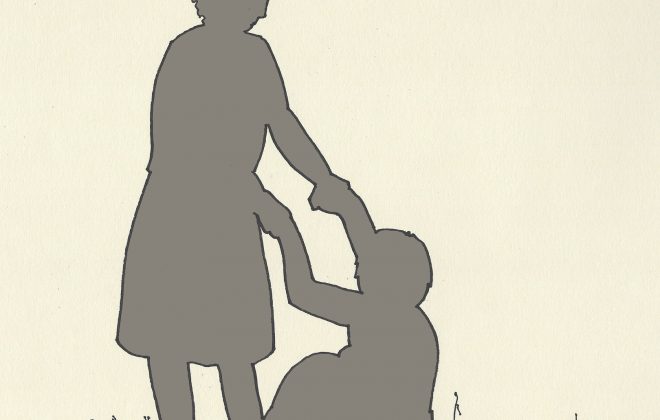

In the plenary, people remained preoccupied with Adisa. Some people realised, that in a kind and steady way, they had been asked to grow up. They had been asked to notice their dependency on someone else to make things better. This dependency drained them of their power of inquiry into their part in what was going on.

After the meeting – what we missed

This insight about growing up marked the end of the workshop. As I discussed our day with my colleagues, we realised we had missed something. It would have been useful to distinguish dependency and being dependent. The dependency needed to be confronted. This is what Adisa did. He asked the leadership to face its thinking and feeling, not his. Asking the subject of your power, to disclose how they feel about that power, without putting yourself at equal risk, is to further subjugate that person.

The moment the senior leadership team recognised its dependency on others to learn, exemplified by what it had asked of Adisa; it was confronted by a second moment. To learn what it needed to learn, it needed others to help and to make it’s thinking the focus of its work. It was faced with its dependence.

Dependence is different to dependency5See Dartington, T. (2010) Managing vulnerability. Karnac, London. See chapter 4. . The latter drains you of agency. The former is a recognition that you need others and it is in the asking that determines how one feels and how one is heard. This was a senior team that was used to knowing what to do and how things were. This was a white group who were leading a diverse workforce. Their whiteness, their shared assumptions, caused them to not hear and not see some people and issues. Like me, they could walk past a statue and not see the history.

A leadership role requires that paying attention to our thinking and the origins of this in our background, gender and culture. We need to pay attention to how we take up our role and authority in groups and teams; notice how this determines what we say and do not say. However, there comes point, if we are to learn more about how we do our ‘leadership’ as an individual and as a group, we need others. Only another can fill in our gaps. The gaps between what we see, what we ignore and what we just cannot see.

After this workshop, I now define a dimension of leadership as a willingness and skill in refusal. A refusal to make others do my learning and a willingness to approach and talk to people in ways that allow them to help me fill in the gaps; and do this without silencing their experience of me (and my group) as part of their problem. A leadership approach Schein calls humble inquiry6Schein, E. (2018) Humble leadership. The power of relationships, openness and trust. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Schein, E. (2016) Humble consulting. How to provide real help. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Schein, E. (2013) Humble inquiry. The gentle art of asking instead of telling. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco..

Notes

[1] See: Kellerman, B. (2004) Bad leadership. What it is, how it happens, why it matters. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Harvey, J. (1988) The Abilene Paradox: The management of agreement. San Francisco, Jossey Bass.

[2] ‘Counter resistance’ is that which seeks to counter the innovation, change or new data. To undermine the emergence of alternative narratives. Tactics may include argument, concept rejection or demand for quick and comprehensive spread, delays in responding, silencing other staff and presence or absence from meetings.

See: Caygill, H. (2013) On resistance. A philosophy of defiance. London, Bloomsbury.

[3] See: Bolton, G. and Delderfield, R. (2018) Reflective practice. Writing and professional development. Sage, London.

[4] See: Argyris, A. (2000) Flawed advice and the management trap. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Argyris, C. 1991. ‘Teaching smart people to learn’. Harvard Business Review. vol. 69(3), no. May – June, pp. 99-109.

Argyris, C. 1986. ‘Skilled incompetence’. Harvard Business Review. vol. 64(5), no. September – October, pp. 74-79.

[5] See Dartington, T. (2010) Managing vulnerability. Karnac, London. See chapter 4.

[6] Schein, E. (2018) Humble leadership. The power of relationships, openness and trust. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Schein, E. (2016) Humble consulting. How to provide real help. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Schein, E. (2013) Humble inquiry. The gentle art of asking instead of telling. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Download this story here. But please acknowledge the source.