This section is about resisting being silenced. As the next slide makes clear, speaking up is hard. There is no guarantee about the consequences. The risks are greater if we continue to frame speaking up as the heroic act of an individual. Some people seem fearless. The ones I have spoken to make it clear this is not the case. The issue is the cost of not speaking up and who they have around them. Any discussion of speaking up has to include a conversation about bystanders. What is my responsibility when you speak up? The second person to say something is equally brave because then it becomes clear that what is going on cannot go on, as if nothing has been said.

The evidence is clear (slide 2). We are cautious about doing anything that risks our sense of belonging in a group. Bullying and incivility is emergent from what is going on ‘inside’ people, between the perpetrator and the recipients or targets, and what everyone else is doing (or not). The question is not what you need to do but what do we need to do?

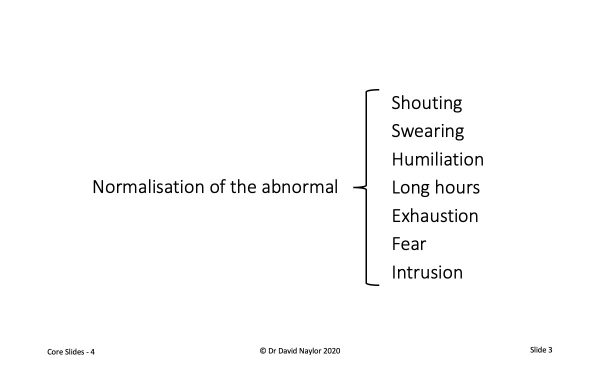

Slide 3 is a reminder that its hard to speak to poor behaviours if these behaviours have become normalised. It is useful to have a conversation about what is accepted around here but people would not like or tolerate in another context.

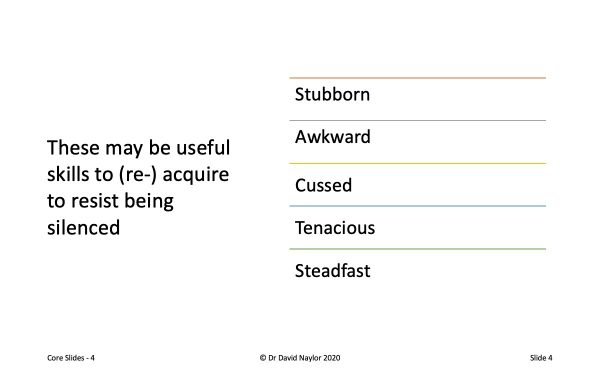

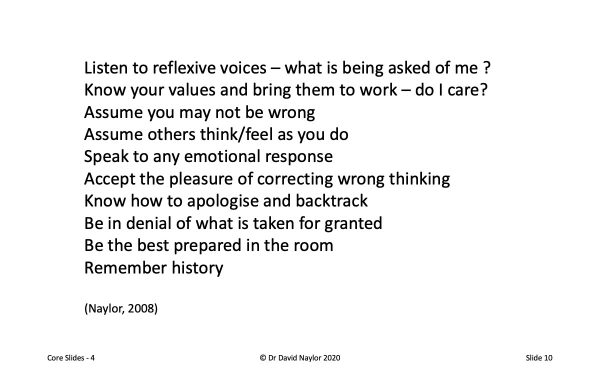

If you want people to question (slide 4), you have to reconsider the value of these behaviours. Behaviours too quickly dismissed as not being a team player, loyal etc. Being a team player is code for agree with me. The failure to differentiate personal loyalty from doing one’s job and the duty to ask questions is what makes people less safe. The behaviours listed are powerful when anchored in a sense of the purpose of the service or organisation. This is what makes awkwardness, constructive.

Slide 5 quotes: Krammer, E-H. (2007) Organizing doubt. Grounded Theory, Army units and dealing with dynamic complexity. Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press, Slovenia. It provides an opportunity to have a conversation about the role of argument and doubt. When is doubt silenced? When is argument avoided? When is doubt and argument unhelpful (and who gets to say this is so)?

It is worth returning to this slide (6) put up in section 1, that quotes ‘The Fearless Organisation’ by Amy Edmonson (2019). As said, talking about psychological safety is not the same as achieving this. This slide can be used to talk about times when it has been present and absent. As in what is going on; who is present; what does sufficient sense of safety look and feel like? Leading to the next slide (also already put up)…

Slide 7 is a reminder that establishing psychological safety is to mindful of what you wish for. As the guide to intervening on poor behaviour argues, you may not like what you hear. How you behave when you hear what you dislike or disagree with is the real determinant of the sense of safety. Again, it can be useful to ask people when they feel they have been encouraged to speak and have met with a less than positive reception.

Schein makes the argument (slide 8) for senior leaders to be curious in his book ‘Humble consulting: How to provide real help faster’ (2016). To accept and act from a recognition of their dependence upon others to fill in the gaps between work as imagined and prescribed and work as done and disclosed. If I need you to be open with me I need to think about how I behave and not insist you are the one who needs to speak up. It is important to emphasise in any conversation, that this dependence is not a sign of weakness or a giving up of authority or responsibility. For a wider discussion of this see my story ‘Not through me, face it in yourself’ here.

Slide 9 gives a quote from Caygill, H. (2013). On Resistance: A philosophy of defiance. Bloomsbury London. It argues that resistance, often bracketed as an unhelpful behaviour to be overcome, is a basic capability of members of organisations. It is a capability linked to ‘argumentation’ (Slide 3). It is a refusal to just accept what is taken around here to accurate and true. It requires stubbornness and a streak of cussedness. It is these capabilities, the willingness to use them and to engage in the resulting conversation that keeps people safer.

If speaking up is required and it is difficult (slide 10), even when bystanders get active, what helps? These final two slides offer some things to think about as one contemplates speaking (or not) and how this decision can be easier if you have a set of good questions that open, rather than close a conversation.

Assuming you may not be wrong is a useful reminder of our tendance to assume as we look around the room that it is only us who think this wrong; rude; offensive; or just plain stupid.

Knowing how to say sorry is a core capability. Most people will forgive if they think the apology is real. A good person on forgiveness is Richard Holloway (see: Holloway, R. (2002) On forgiveness. Edinburgh, Canongate).

Being well prepared is key. Knowing the facts; the process; the context better usually triggers confidence in one’s perception, particularly if they go against the prevailing flow of the conversation.

Remembering history may seem an odd reminder. Not everyone would agree but the process by which bad things have been done to people in the past invoke the same sorts of processes we can see in organisations. Bad things tend to happen if we marginalise certain people; silence them, and attribute what we cannot stand about ourselves to them. The question is if not now when, if not me who? Remembering this applies to the person who speaks first and especially to the person who is thinking about speaking next in support.

It is worth keeping in mind that an excessive focus on the personal capabilities is to lose focus on how power and right ways of thinking are embedded in organisational structures and ways of working. So, you can have powerful and heroic interventions and someone needs to say ‘and why is it so hard to say this?’

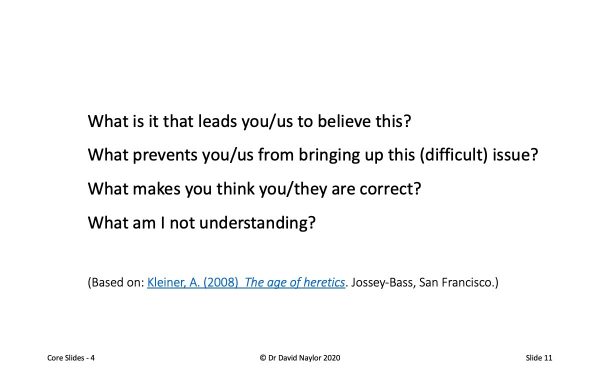

The final three slides (11, 12 and 13) offer questions that can open and pursue an inquiry-based conversation. The four questions on this slide are based on: Kleiner, A. (2008) The age of heretics. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. A conversation that is not about telling people what to do (instrumental talking) but about curiosity about the thinking that underpins our assumptions and behaviours. The skill is keeping it at the level of ideas and not speculation about the character or personality.

It easy to put up questions and avoid the challenge of context. These questions are confronting and the recipient may not be used to being questioned. It can be useful to talk in inclusive terms (eg what leads us…what are we not understanding etc.).

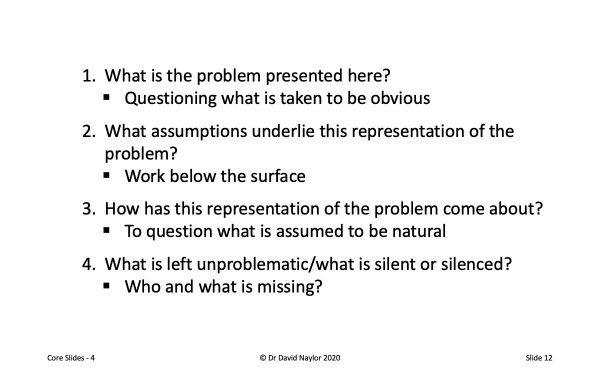

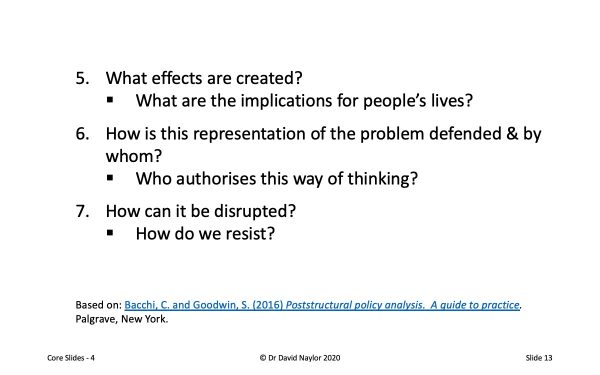

The purpose of asking these seven questions is to examine thinking; how this thinking ‘produces’ problems and solutions; and how this thinking is situated in our prior learning, experience gender and culture etc. These questions can be asked out loud in a meeting or internally, as the means to build the sense of agency required to publicly question what is going on. As in, having asked these questions in my head, what is proposed challenges my beliefs about what is right. So, what am I going to do about that?

You could also imagine a meeting in which asking these sorts of questions is a way of embedding doubt and taking action. Reflecting the culture of argumentation described in slide 3.

These seven questions are based on: Bacchi, C. and Goodwin, S. (2016) Poststructural policy analysis. A guide to practice. Palgrave, New York.

Download my slides for ‘Refusing to go quietly’ here, but please acknowledge the source.