This section can be used to argue the negative effects of bullying and incivility. Effects on our capacity to think; collaborate; be present; and speak. Effects that cost the NHS billions each year, suggesting the Finance Director should be front and centre in any intervention to reduce the use of these behaviours (see my story ‘The case of the missing finance director’.)

The research builds a case to pay much more attention to how people speak to each other, an approach building on the insights of the Sign up to Safety campaign in the NHS (2014-18). Here the focus was on conversations one might have around the kitchen table. Informal; meaningful; emotional; and practical. In contrast to being told to shut the **** up.

It is important to keep in mind that bullying and incivility can be used interchangeably in the literature and any intervention to improve things. They are similar but bullying is of a different order. There are usually witnesses, whose bystanding compounds a sense of isolation. And incivility does not quite describe the trauma of being told to shut the **** up in a public meeting.

Slide 2 quotes from the NHS Interim People Plan (2019) and can be used to have a conversation about the gap between the intention and what we know how to do. Saying we want things to be different is not the same as things being different. For all our good intentions these behaviours endure. While they cannot be eradicated, we need to look at our thinking about why we use them. First, this is the evidence to support an argument for such an investigatory approach.

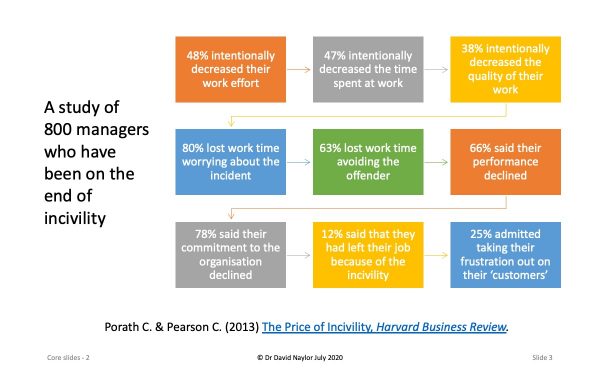

Slide 3 quotes evidence from a study published in the Harvard Business Review entitled ‘The Price of Incivility’ (Porath C. & Pearson C, 2013) that supports the argument that incivility is a part of the ‘normal‘ organisational experience and it has significant effects on our capacity to do the work we are paid to do and want to do.

Schilpzand et al in ‘Workplace Civility’ (2016) in their review of the literature offer (slide 4) a simple explanation of incivility to support a conversation about what people have experienced and recognise as incivility around here. You have to be alert for the normalisation of what others, in a different context, will hear as offensive. Or what people already marginalised/silenced may experience.

In ‘The role of appraisals and emotions in understanding experiences of workplace incivility’ Bunk. J and Magely, V. (2013) note (slide 5) that the low-intensity comment makes it important to be alert for the offensive to be normalised. Listen out for comments like: ‘I was just being clear’; ‘it was how I was spoken to’; or ‘aren’t people a bit sensitive these days?’.

The quote on slide 6 from Ruskin et al (2015) in ‘The impact of rudeness on medical team performance’ suggests that these behaviours land badly with us and have observable and measurable effects on our sense of well-being. So, if you shout at someone to work harder you are not helping.

Riskin et al (2015) further note (slide 7) that if our thinking is attacked it then effects our capacity to collaborate to create effective teams. Given ‘teaming’ is argued as a basic capability to keep people safer, productive and creative, this link needs to be talked about (see ‘Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy’ by Edmondson, A., 2012). For example, how much attention is paid to the facilitation of a team? Or, is it about bending people to the will of the Chair?

Slide 8 confirms that being on the receiving end of poor behaviour drives us inward, part of the loss of attention that is risky and wastes people’s know-how. It is a way we can misdirect ourselves – it is my fault, rather being curious about the purpose of such behaviour. As in, what is being silenced or ignored as we talk like this?

The BMA research (slide 9) into doctor’s views of working in the NHS ‘Caring, supportive and collaborative?‘ suggested some causes of incivility. This slide opens a conversation about explanations, so linked to the previous slide. ‘Pressure’ can be taken as axiomatic and arises from the way things are organised in relation to the purpose. Therefore, raises a question about who is doing the organising and the extent this work can be incorporated into any ideas about causation of poor behaviours. As such, links to work as imagined/prescribed (slides 3, 4 and 5).

The slide also opens a conversation about how hard it is to resist these behaviours. It is not a simple as trying harder.

Slide 10 quotes data from the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (2019) and makes the argument that bullying and incivility is disproportionately experienced by BME staff. A fact. The slide can be used to explore the assumption made in ‘Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organisations’ (Cortina et al, 2011) that incivility, racial and gender harassment have a lot in common. Incivility can be presented as if it is neutral, as in applied to all. However, it is also the case that incivility is a way of covertly expressing racial and/or gender bias. I am rude in an everyday sort of way and I am rude to you in particular, because you are a black, female doctor.

The impact on wellbeing is compounded by the virtual invisibility of this process to the perpetrator and bystanders; leaving the target wondering what has just gone on. A confusion that amplifies the self-doubt, already identified on slide 8, as an effect of these behaviours (see ‘Racial microaggressions in everyday life’ by Sue, D.W. et al, 2007).

This is a conversation to evidence the general effects of bullying and incivility. A call for action. It also needs to be a conversation that explores the differential effects of these behaviours on individuals and groups already subject to harassment and discrimination. Such people face a ‘double jeopardy’, as argued in ‘Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women’ (Berdahl and Moore, 2006).

Slide 11 backs up the call to action. Research confirms this behaviour costs. See ‘Evidence synthesis on the occurrence, causes, consequences, prevention and management of bullying and harassing behaviours to inform decision making in the NHS’ by Illing et al, 2013 and backed up in ‘The price of fear: Estimating the cost of bullying and harassment to the NHS in England’ by Kline et al 2018. If this was through fraud or stealing, there would action. This is an opportunity to open a conversation about why sensible and ethical people find themselves seeing the cost of bullying and incivility as in some way different to stuffing the department photocopier into the back of my car, late one wet and windy Friday night, watched by a small group of onlookers.

This slide and conversation set up the next section on how we can be silent and silenced.

The literature is persuasive and underpins the case for action. It should be read and discussed. Slide 12 gives some further references.

Download my slides for ‘How we talk matters’ here, but please acknowledge the source